For most of my childhood, we did not cross the Great Divide, much less go abroad. My orientation was north to south, up and down the coast. Beyond memory fragments from a couple of early childhood trips, the East was a place for costly short long distance phone calls, and stories my parents told from their pasts before they knew each other.

Instead of travelling far and wide, we went to the mountains, in the northeast of our state of California. Memory of these trips seems clear now, though that may only be because the gaps in recollection are filled by the layering of fragments from dozens of similar trips over many years, like those of any familiar road. Some day in mid-June my mother would roust us out of bed early because we needed to get across the central valley early, to beat the heat. We’re off, she might say as we backed out of the driveway, like a herd of turtles. We were packed into a dark green 1952 Chevrolet carryall, which today would be called a van of some kind – two adults in the front, though a third person could fit in the middle on the wide bench seat, no seatbelts; three children (the carryall expired before the fourth arrived) in the back atop a double mattress itself atop our belongings for the summer. Up the Bayshore freeway, across bridges and coastal hills to the heat of the valley, north through the valley and then winding north-eastwards to Oroville. Oroville sits at the foot of the mountains, so if you follow the highway northeast from it, you climb quickly. In this case you follow the canyon which the North Fork of the Feather River has cut deep through Sierra granite. All told, from home near Palo Alto, this was seven hours driving, if we were lucky with a stop in Marysville for lunch and a milkshake. That’s the start of some canonical, platonic form of summer; in life the timing varied and sometimes my father would be teaching summer school or taking a course himself, in which case we might not take this particular trip at all. Still it was a pattern, which started the summer I turned six. We camped there on Indian Creek for six summers, on land of my father’s friend Jerry. A cabin still gritty in its cracks with silt from the latest flood, came on the market and we bought it. We still have the land on which the cabin sat, my siblings and I, our parents having left this world and the cabin having burned down, taking poor Weezie with it in her sleep, though she is not part of this story.

The summer best remembered is the one when I turned nine, and that year we actually arrived at Indian Creek not up from the south but down from the north, where my father had spent the year finishing up a master’s degree in Eugene, Oregon, and, our own house having been rented out until Labor Day, we camped for three uninterrupted months by the stream on sandbanks new-heaped by what was in those gentle times thought of as a great flood. We had come down from Eugene, our old carryall pulling a tarp-covered trailer, along the gravel detours which paralleled the emerging bits of I-5. Towards the California border my mother fussed to tidy things up, ostensibly because the border station where they ask if you’re carrying fresh fruit might still be intercepting impecunious migrants, ain’t got the doh-re-mi, thirty years after the dust bowl and at the wrong end of the state. A device, I am sure, to motivate her children to achieve some modicum of presentability, though a taste for dramatizing a situation cannot always be distinguished from actual anxiety.

Between two oaks standing incongruous on the wrecked river bank my father built what would serve as our kitchen counter, with a shelf below it, a Coleman white gas stove on top. It was not really so rustic, as it was only a five minute walk to the well house next to Jerry’s, where we had use of a fridge and toilet and could draw potable water to carry back to camp; there was a shower there too but since we swam in the creek at least once every day we could have lived without that. Ann and George and little Sarah slept in a tent, Jenny and I under the stars, on our backs staring straight up at the meteor showers of August. A little further from the stream, just above the sand and river rock, was a dense stand of young ponderosa pine, or if not young at least small, since on that meagre ground it grew slowly. My father would say to me, Let’s add some nitrates to the soil, and we would go together to piss near the feet of some grateful tree. His father had had a different lesson to pass on about pissing, telling him when that task was finished, if he shook it more than three times he would go blind; or perhaps, to Hell, I can’t be sure if as told to me it was blindness or damnation and now there’s no way of checking. Either way, the difference in lessons attached to that simple act, from one generation to the next, offers a sliver of hope for the human species.

1968, the summer I turned fourteen, we didn’t go to those mountains in the northeast of the state because my father was teaching a course for biology teachers at Humboldt State, so we went instead up highway 101 through the coastal redwoods and to a rented house north of Arcata, near McKinleyville, on a bluff overlooking the Pacific. It had been advertised as four bedrooms on a cliff above the beach, a description that omitted one of those rooms being packed solid with the absent owner’s belongings, and the freeway (albeit not a very busy one – it was one of those remote rural freeways that American highway funding has built because it must) at the foot of the cliff, between us and the beach. The prevailing northwest wind brought fine Pacific air, though on many days with a dose of rotten egg scent from the pulp mill in McKinleyville mixed in. The landlady was off doing some good work with migrant farmworkers in the central valley, not much doh-re-mi, and couldn’t be begrudged the occupied room, and the house was pleasant enough.

We had one car with us, which my father took off to work most days, so there was not much to do but go down to the beach, through the culvert that passed under the freeway. Put away any visions you may have of sun swimming or surfing, this was the cold and unsafe ocean of northern California. People did come to that beach to dig clams, and I learned to see evidence of them from the surface condition of the wet sand, but we never dug any. Once or twice I went up the road, away from the beach, in search of blackberries.

As the eldest child and a boy I, alone, was able to escape, finally, after Kenny came to visit.

Why do you say escape? asks Sarah, I liked it there, going to the beach with mama. I, though, was a teenager: time to go.

A year older and my undoubted best friend since ever, Kenny usually came in and out of my life along with his parents and siblings in a VW van, back then called a bus, and before that when I first heard of such, a microbus. They moved up and down the coast, not just taking trips but changing residence from one year to the next. I don’t know whether Kenny’s stepfather Victor was restless or just fell out with people at work, I suspect the latter.

Kenny’s mother Kay always spoke glowingly about the present and, as I came to know her again in her old age, bitterly about the past, especially the men in her past. Bitterly, that is, with the exception of Paul, the love of her life and Kenny’s unacknowledged father who in his own old age, which came a bit before hers, left his wife and their house on the hill to live with Kay in a trailer near the sea, near Santa Barbara where homes near the sea have a bottle of Johnson’s Baby Oil near the door with which to take off the tar that leaks out of offshore oil wells and accumulates on the beach, and where Kay nursed Paul through his final illness. In her own old age Kay of course had more past than future, or perhaps I had just become old enough myself that I was somebody she could unburden to, so I heard a lot about those men when she visited me once in London. There she endured walks with me which must have been excruciating on her decaying joints, but when I walk I can be heedless. She told me of arriving penniless with the three boys (was baby Tori with them yet?) in El Centro, a poor agricultural town hard on the Mexican border where Victor was starting a new job. With no help forthcoming from Victor, she sought out the local rabbi and with his help established credit and was able to set up housekeeping. Thus in one vignette she could combine portraits of feckless Victor, her resentment at being his blonde shiksha trophy, and her personal resourcefulness and triumph.

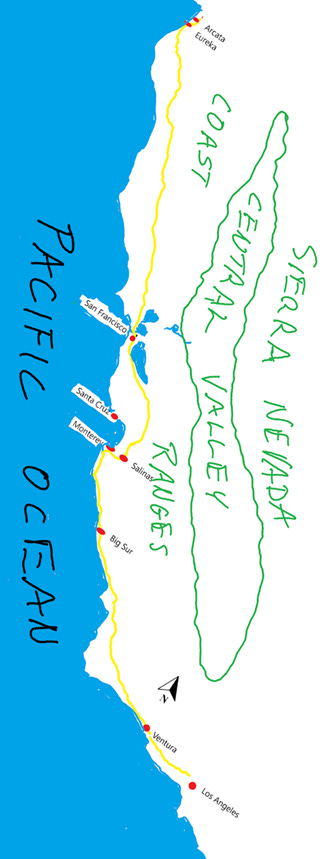

The map in my head was filled with the names of places they had lived, strung between Washington State and the Mexican border: San Carlos where we first met them (before Victor), Walla Walla, El Centro, Susanville, Napa, Santa Cruz, and a couple of different houses rented in our own little neighborhood of ex-summer cabins in the hills southwest of Palo Alto; Corvallis came later, and now and then someplace down in Mexico, with Mark and Eve. The year I was in first grade and Kenny was in second we were in the same school, I know because I remember talking with him in the playground there, about what I don’t know. I know just that we always talked, looked forward to talking, when we saw each other, which in most years wasn’t much because his family came and went. I don’t know how Kenny reached us that summer of 1968 – I don’t remember seeing the microbus. I do know how he and I left, which is that my father took us to the Greyhound station in Eureka, just beyond Arcata on the south side of Humboldt Bay. The first bus took us to San Francisco where we got another to Monterey. From San Francisco, Kenny and I couldn’t get seats together and I sat next to a woman who shared with me her paranoid, bigoted view of the world and simultaneously scribbled it down over many pages of dense black ink, channelling from some dark source of revelation, which she gave me as a gift when she got off in Salinas, Lord, I’m glad she slipped away.

I kept her deranged pages for several years, filed along with letters from various friends and relations. I didn’t like what she’d written and I don’t remember it as even coherent, but it seemed a document of something in my life, my travels. Many years ago now it fell to the occasional thinning out of files, the purge of unpleasant or insignificant things past. I don’t actually have many documents of my past.

Having documents, of course, might not help me write this. I am thinking now of a very bad book I read by Norman Cousins. I had the privilege of working with Cousins on some political projects when I was in my early 20s so I’ll drop his name here, quickly now while a few others are still alive who remember it as a name worth dropping. He loved dropping names himself. Once in a committee meeting we were taking a break and he was glad of the break because it gave him a chance to ask those who had stayed at the table rather than going out for a smoke, “have I told you about my meeting with Arafat?”, which he had not but then did, though all I remember is that he was driven around Beirut blindfolded in the windowless back of a van until completely disoriented, then there he was in a safe house with the man, what they said to one another has long since left me. Cousins had been famous, from 1940 up into the 70s, as the editor of The Saturday Review, a magazine of the arts and current affairs. He was a leading light in the organization I was working with, and in the mimeograph room was a supply somebody had purchased and then failed to sell of his The Improbable Triumvirate: John F. Kennedy, Pope John, Nikita Khrushchev. Perhaps it is one of those copies that found its way to an online bookshop for fifty cents plus shipping, when memory of its cover led me to buy a copy. This book tells a remarkable story, better than a blindfold meander in Beirut and far far better than most of us will ever have to tell: in early 1963, after the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK asked Cousins to meet with officials in the USSR and the Vatican, not in an official capacity but to get their measure on some ideas for ending the arms race and the cold war. Cousins trotted off to Rome where he met with high officials at the Vatican, then to Russia where he met with Khrushchev himself at his Black Sea retreat. The talks were promising. Then Kennedy was shot, Khrushchev was ousted, and Pope John died, so of course the mission came to naught. A great story, but a bad book. If you should ever waste your time reading it, you may come away as I did with two impressions. One is that Cousins works very hard to tell us how clever and important he was, how important he was to JFK, and how persuasive he was with Khrushchev. I have in my life been accused of hiding my light under a bushel and it’s possible that I’m simply hoping to see the same in others, but it does seem to me that if you’ve been asked to carry out that particular mission, your own importance is not something the rest of us are going to question, and insisting on it kind of spoils the story. But even more disappointing, this story from the pen of such a renowned editor, is that alternating between the generous ladlings of self-importance, the bulk of text reads as if Cousins has assembled it from his appointment book, the minutes of meetings, resolutions adopted, and lists of those attending. He had his records, and he used them, plod plod plod. There is no danger of that in what you are reading now.

I take heart, instead, from Patrick Leigh Fermor’s wonderful memoir A Time of Gifts. It is the story of his walk from the Netherlands to Romania in the 1930s – subsequent volumes see him to Istanbul and Athens. He didn’t write it all down until the 70s, when he was in his 60s and had long since lost the journal he had kept on most of the trip. This absence of source material gives his narrative a funny texture and imbalance. He keeps that narrative in the order of his footsteps, chronological and geographical unity. But what he relates we can divide in three: first, memories of certain physical events (a night in an unlocked jail cell in the Netherlands, a barge trip up the Rhine) and of encounters with certain people, vivid memories such as one might well retain many decades later; second, a bit of political and social context, in which he combines remembered events with retrospective analysis – he’d remember differently, or maybe not at all, what he saw then of the Nazis had that not led where it did; and, third, a detailed appreciation of certain natural features and buildings – the Rhine and the Danube and, in particular, baroque structures, baroquely described – which I expect were actually revisited in middle age, and described anew as he was writing the book. Lack of documentation made it a much better book than it might otherwise have been. I can hope.

I do have, still with me, two letters from Kenny, sent from his brother Chris’ address in Ventura. In one of them he proposed this very trip we were taking. He had also heard that I was wearing my hair long – I was one of two boys in my middle school with hair that was then considered long, though the other boy’s was not as long as mine and neither of ours was what would be considered long today. It is hard to express now how contentious the silly matter of male hair length then was. Don’t cut it!, Kenny said; his was long, too, by the lights of the time.

In Monterey we started hitchhiking south on highway 1 towards Big Sur, where Kay and Victor were camped. It was late in the afternoon; a lot of fancy cars heading for Carmel passed us by. Around dusk the police took interest and we were in a police station. The police got on the phone and at this point in the story I have long remembered them getting my father on the other end of the line. Jenny, reading now, reminds me that we had no phone in that house – the landlady had a phone but it was disconnected for our summer of tenancy; I had had no phone number to give the police, only an address. The police in Monterey would have called the McKinleyville Police Department if there was one, more likely there wasn’t and they called the Humboldt County Sheriff, so I’ll say it was a deputy sheriff that was dispatched to find my parents. What Jenny remembers is the officer showing up at the door, with news that Kenny and I had been found in Monterey. It is then that the reassurances I had imagined coming over the phone line were delivered, presumably to the deputy who would have relayed them by radio, or perhaps he handed the radio handset to my father: yes, my parents knew we were headed that way. Yes, Kenny’s parents were in Big Sur, and had no phone there. Yes, it was all fine. The police took us, two well-spoken white boys that we were, to a park near the highway where we could roll out our sleeping bags.

Was it there, looking up at the stars, that Kenny reminisced about my father’s voice? When I was small my parents always read us stories in the evening. Actually, since I am the eldest of four and my brother Matthew is eleven years younger, I got to listen to stories until I moved out of the house, heard each Winnie the Pooh story dozens of times over the years, the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings a couple of times at least. But, when small, and with the excitement of having a friend sleeping over, to get us to sleep it helped to have the light out, so no reading, and my father would tell us stories. He was not, when putting us to bed, telling stories of his own life, and the other stories he knew to tell were those of the Norse myths, stories I guess, since we had a copy of it somewhere, he’d learned from Paidric Colum’s Children of Odin, but he never read these to us only told them, and we called them Thor Stories. Thor, Baldur, Loki, Odin, Freya, giants, dwarves. And what Kenny remembered as we lay in the dark under the stars was my father’s voice as he told us Thor stories in the darkened room when Kenny was spending the night at our house as he sometimes did. It is of course a voice I remember, deep and, most of the time and certainly at story time calm. It pleases me now to remember Kenny’s remembering it.

Kay and Victor were camping at Big Sur to be near the Esalen Institute, Mecca for Gestalt therapy and human potential. Victor had once been a journalist, then a social worker, and was now easing himself into private practice as a talking therapist; he was witty and had a distanced avuncular manner by which he claimed understanding without saying much. I believe that in gatherings at Esalen it would however have been Kay, beautiful and intensely focused, with a way of repeating back to a man what he had just said in a way that endorsed his brilliance, who would have done the real selling for the family firm. I knew nothing of this then, though, and I remember nothing of Big Sur on that visit. I’ve gone back since, several times, and can report that it is every bit as beautiful and special as people tell you: the drive along the coast; the cliffs, the sea and the beaches; the walking trails leading inland up the ravines that come down to the sea. The bookshop memorializing Henry Miller is a magical place, though I’ve little time for Miller’s writing. Nor do I remember how long we stayed, there with Kay and Victor, except that it wasn’t long. Soon we were further south in Ventura – how did we get there? - with Chris, with whom we drove still further one day to Hollywood, where we saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, just out, in a movie theatre that I think was very large, Hollywood large. I also do not remember how I got back home from Ventura.

After that summer, Kenny got a motorcycle. Kenny had always carried some extra weight, was asthmatic, wore glasses; his mother later told of his pleasure at the way girls looked at him when he was on his bike. He never got his full license, however, because less than a year after I last saw him, on his way from Big Sur to the DMV in Monterey to take his test, along that beautiful coastal highway 1, he crashed and died. The highway patrolman called his mother in tears. She called my mother. There was a funeral – rather, a memorial service – in Santa Cruz with us seated in a circle and people taking turns with recollections and readings, including one from a poem Kenny had written about spraying his sister with water from a garden hose, water rhyming with hadn’t oughter, and little Tori snorts and sneers / like when my Honda shifts its gears. After the service Kenny’s presumed-father, the straight-laced or in the spirit of the time up-tight ex-husband Kirk, told one of his surviving sons “that was just like your mother”, not in a pleased way. Then we gathered in a house where Kay and Victor must have been living, where again we sat in more or less a circle, around a room. We listened to music, of which all I remember is Arlo Guthrie’s motorcycle song (“I don’t want a pickle / I just want to ride on my motorcycle… And I don’t want to die / I just want to ride on my motorcycle”, the pronunciation of “cycle” adjusting to what is needed for the rhyme) playing more than once. Or maybe it’s just played ever since in my head.