Somewhere around the world floats a raftful of memorable souls fate has forced me to abandon. How to grapple this human flotsam to me as I am swirled from hemisphere to hemisphere I have never found out. Patrick White, Flaws in the Glass.

Living in Europe in middle age, visits to California have usually been a matter of flying, preferably Heathrow to SFO nonstop, so the transcontinental part of the trip, the three-or-more day land journey from New York to San Francisco, is replaced by a few hours over Greenland and Canada. When I was young though I did the land journey several times, variously in a car, U-Haul truck, Greyhound, train. Those trips provided some good memories: conversations with people in the next seat, overnight stays in campgrounds or somebody’s spare room or on their sofa, endless open spaces between Reno and Chicago; snuggled up with Eileen on an Amtrak – no, more than snuggled up, I can’t be quite so Victorian in my description and I have always wondered how much we tested the patience of the other passengers who may have been politely pretending to sleep and not to notice what we were up to. But then we ourselves had finally fallen asleep, somewhere in Nebraska, where in the wee hours the train derailed and, after assembly by emergency workers in a school gym, we were put on a flight to Chicago to make our connection to New York.

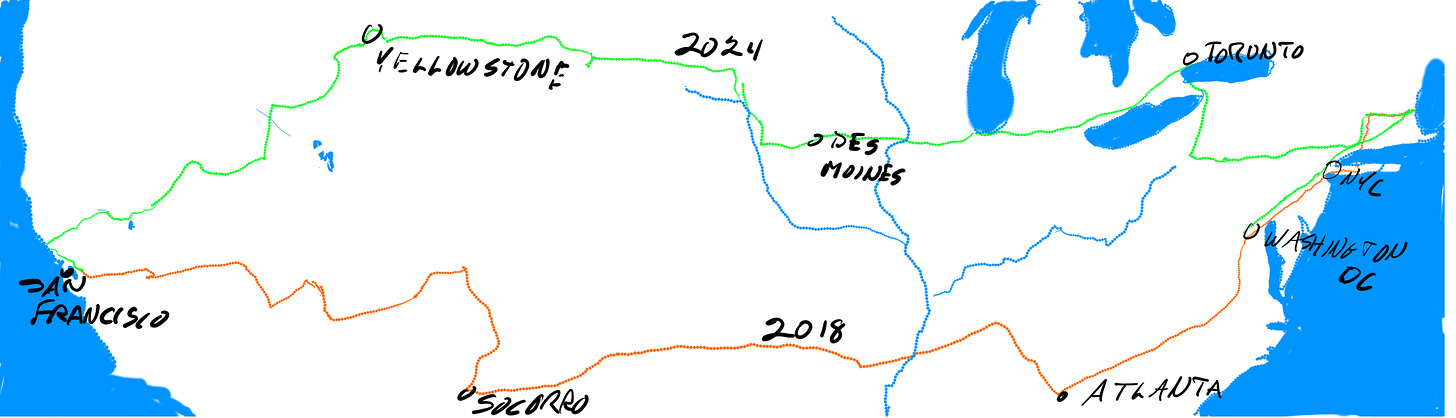

Though such fragments of memory are precious they also remind me how little I remember – many trips by different modes with different people stopping in different places, the remembered parts are how small a fraction? A few months ago in this year of 2024 I was in Washington D.C., about to turn seventy, at the start of another transcontinental trip, this with my son Leonardo. We had dinner with some high school friends of mine, people I first knew when I was the age Leonardo was at the time of that dinner. Among them was Michael, with whom I had driven across the country in my parents’ VW bus when I was eighteen. I was delivering him to his aunt and uncle who lived near Washington, and they would in turn deliver him to college while I wandered off without much plan, as was my wont. I had always cherished memory of the trip, but that was easy because there was so little of it: a snatch of conversation we had while watching the locals in a coffee shop in Wyoming; staying with my uncle, my father’s little brother John Howard (the middle name used always to distinguish him from their father, John Gustav), in Minneota, Minnesota, meeting other young people at the swimming pool in that town, and being shown the hogs on John Howard’s farm. Nothing more, really. Michael remembered, and now with his help I have replanted in my own memory after five decades’ absence, watching the summer Olympics in a motel room in Wisconsin, drinking beer which I could at eighteen then buy in that state, and using the motel bed as a trampoline, perhaps in sympathy with the gymnasts on TV. That would have been our first stop after Minneota. All I had remembered of that Wisconsin stop, before Michael jogged my memory, was that getting out of the car I met warm, humid air, and knowing that the humidity had impressed on me that we were no longer in the West. I had that image - there may also have been fireflies - but didn’t place it in any particular trip; also, no motel, no Olympics, no beer, no Michael. There are, buried somewhere, hundreds of such episodes from my various trips across, about which I can’t tell you: this being a memoir, the first editor is Mnemosyne, a Titan with whom I have little influence.

It is the journey, not the destination. So we are told, often, but I’m not so sure. Most of the land journey from coast to coast is bleak, it is grasslands or desert which if seen slowly and close-up would be beautiful in detail and in the contrast between the detail and the big-sky panorama at least for a while; from a car, a train or a bus on the freeway the detail is lost entirely and monotony alone is left. For these lands to become worth seeing you need to stop, and then what state you’re in – is this stop part of the journey, or is it a destination? - becomes unclear. A journey may be point to point – that Heathrow-SFO nonstop – in which case, emphatically, meaning and beauty are found not in the journey itself, in the time spent at airport security or sitting cramped in a flying aluminium tube; if they are to be found it will be at the destination. Crossing a continent by land this distinction is blurred a little, because meaning or beauty may be found at many points along the way, dots which, if you stop at one for a while, you may think of yourself as connecting with the ones before and after. It may be that I’m abusing the image here, and that sayers of it’s the journey, not the destination mean in “journey” to include all the dots we connect before the final destination of death; that might have worked for Dante – midway through life’s journey, that’s how the first line gets rendered into English, I haven’t read it, together with abandon all hope it is all I know of the three volume Comedy – because his subject was the afterlife, with all of life a journey towards that eternal ending, while for a secular scientific lad like myself who treats death as final, the blithe journey not destination too easily reduces to the claim that meaning is found in life, not in death, which I hope is uncontroversial and if that’s what is meant then the saying about journey and destination is as trivial as it is worn out. That, Humpty-Dumpty told Alice, is Logic. A bit of logic I need because I have journeyed a lot from one point to another, one home to another, and it leaves me sometimes wondering where I am, where I should be – I can take some consolation in saying, “all those places I’ve been, those points, they were destinations”.

Where the journey does have something to offer, it is because you find something, or someone, who makes you forget that you are moving through space. I’ve had several good, long conversations on airplanes, and met that way one friend with whom I’ve stayed in touch, others with whom I regret not having stayed in touch. Or on the bus: taking the three day Greyhound ride from San Francisco to New York a couple of years after my drive across with Michael I sat beside a Mexican-American girl from the Mission District, sixteen or seventeen. Chicana, she said; a Brown Beret, she also said, holding her head to somehow suggest one on top of it at rakish angle but not I think expecting me to believe she had a role in that Chicano group which for a few years aspired to parallel the Black Panthers. Or perhaps she did. We talked and cuddled and kissed a little. “You’re a gentleman”, she said; I had obeyed her direction and stopped touching her breast; “you’re a gentleman”, she said again, cementing the deal. We shared the cardamom cakes (high protein, said the cookbook) and oranges I had brought, and she got off in Chicago or Cleveland. For those 48 hours those two seats were a destination, a place, and I have no memory of the scenery flashing by. The rest of the trip to New York was a dreary Journey, and on the return trip to California I scrapped my bus ticket and accepted the offer of space in a car with two other young men and we took turns driving, through the night; about that my memory is simply that the trip happened, we sped along. Conversation with Phil, whose car it may have been, did happen, but even if a conversation in a car is part of a journey, it would have happened anyway if we had spent the same time not on in a car but sitting in a restaurant in Reno. Phil, who I knew through the shared political interests which had taken me to New York for a conference in the first place, told me how he had once moved to Las Vegas for his health – bad lungs, clean dry desert air – and had taken up card-counting at the blackjack tables, making money until he was banned from all casinos. When we did reach Reno, and again passing Tahoe, he was tempted knowing there were tables there, cards, and perhaps he wasn’t known in this part of the state, but he opted not to make either of them a destination and we sped on across the Sierra Nevada and down the other side, to San Francisco.

When I was two or three my family, then four of us, took the train to visit my father’s family in Minneota. That meant a train up the West Coast from Oakland to either Portland or Seattle, there to catch the Great Northern’s Empire Builder eastward, across Washington, a bit of Idaho, then Montana and North Dakota, where somebody probably came to pick us up in Fargo. That much I know from the map; I actually remember only two things: being taken, perhaps because restless, to an observation car which was not the then-usual one at the tail end of the train, but one with windows overhead, the better to see the mountains and canyons through which we passed. I don’t remember those views, though, what I remember is the car and its windows, so I’ll claim it as a destination, a point where I was stopping, even if the point itself was moving; similarly, the dining car, where the children’s menu was also a stiff paper mask which transformed you into the Great Northern Railroad’s spirit animal, the Rocky Mountain goat, with terrific horns. On another – I suppose the other – trip East when I was small, we drove, stopping in one direction or the other in Minneota, but getting also to Maine, where on the coast I remember the red barn at some cousins’ summer place – a color I have recently verified with those cousins, so this fragment of toddler-memory holds true - and my bedridden grandmother’s effort to greet me through a film which I know, having been told, was an oxygen tent and that the bed was in a hospital in Northampton, Massachusetts. Memories of the journeys between these points have not been stored, and probably don’t deserve to be.

After those two early crossings I stayed, for the rest of my childhood barring one summer in Texas, on the West Coast, not getting to the East until the drive with Michael when I was eighteen. In the twenty years after that I made several crossings in addition to those mentioned above, in each dashing from one coast to the other, stopping mostly to eat and sleep. At forty-one I moved to England, and crossed America only by air until a few years ago when I, my wife Simona, and our son Leonardo decided to take a Road Trip. It was, for me, a way to renew connections with some people. Like Patrick White, whose life was scattered across Australia, England and points between, I have lost touch with a raftfull of memorable souls in the course of moving from California to the East Coast to England and now to Italy. I cannot say that “fate has forced me to abandon” them – indeed I’m not persuaded by this self-justification from Mr White, who knew well how to pick up a pen and write, he collected a Nobel Prize for just that and could have employed it on the odd postcard to stay in touch with some on his raft, as I could have with mine. I have had some need, one I don’t understand but won’t stoop to calling “fate”, to move on. And maybe, some day, to drop by again.

“Life is meals.”, James Salter declared in Light Years, “Lunches on a blue checked cloth on which salt has spilled. The smell of tobacco. Brie, yellow apples, wood-handled knives”. Life is Meals, I love the phrase, though more gripping for me than Light Years was his final book, All That Is, told in the close third person which is to say almost but not quite from the point of view of the central character, who turns out [spoiler!] to be not mistreated but vile; the art of the book is the time it takes the reader to see that, and even when you do see, it is not clear whether your recognition of the character’s character was so delayed just because the narrator had cleverly hidden it from us, or because the narrator is the character and doesn’t know himself, and presumably never will; in either event, we (or, at least I, this credulous reader here) don’t see it until those fragments of his life we have been privy to pile so high that rendering judgement is something we can’t avoid. Perhaps that should be put as a warning label on any tale, written down in a tone that invites trust and sympathy, of a person’s stumbling and bumbling through life.

But – let me not again digress from this! - life is meals. The late John and his wife Kay Salter took that phrase from his novel and used it as the title of a book with 365 short chapters, a book of days, each a reflection on food, eating, and in particular eating together. So many of the destinations, the points I connect, are meals, the meetings with old friends and the making of new ones. The road trip of 2018, six years ago as I write, I can count through by meals, and I remember little else: the restaurant in Boston where Margot took us; the overwhelming Brazilian all-you-can eat where we stopped as we drove out of that city to the north, foolishly amplifying jetlag with overstuffed stomachs; being told, somewhere along Massachusetts Route 2, that there was no espresso to be found west of that point – incorrect, as it turned out, and we found that we could escape the Starbucks hegemony by entering “espresso near me” into Google Maps as we crossed the country; Peter and Karen’s kitchen in Amherst, and the table on their screened porch, for salmon and vegetables brought from Whole Foods, and miscellany from local farm stands; a beer in that kitchen, and so I remember beer with Peter and his first wife Dorie in their kitchen when they lived in Denmark, where the beer was delivered by the brewery in a re-usable crate of re-usable bottles, like milk was when I was a child; in Hamden, Connecticut, my cousin Sally’s chicken salad for lunch, in her living room; a drive, a ferry across Long Island Sound, and another drive later, the smells of industrious baking in the kitchen of Ellen and my cousin Reiny, who later played his guitar and sang for us; the bagel place, a novelty to the two Europeans I had in tow, across the street from our AirBnB in Brooklyn; another lunch with another chicken salad in the back yard of my cousin Ann, Sally’s sister, in New Brunswick, New Jersey – and let me say that the two salads were equally excellent; a barbecue at my cousin Debbie’s in the Washington suburb of Bethesda, with her brother Jeremy and his now-wife Marcia, and more playing and song from both Debbie and Jeremy; at Gordy and Maryann’s in Chappel Hill, a dinner, I can’t remember what but it was good, which he prepared in their beautiful, theatrical open kitchen as we chatted over the counter, and had served in the equally beautiful and theatrical dining room of their modernist house in the pines. I’d never met Maryann or Gordy before, she’s somebody Simona knew through work, but in that kitchen while Gordy cooked I pitched Maryann an idea for an academic paper which she and I and Simona did, and it made a bit of a splash in the small academic pond we inhabited. That house is gone now, they’ve since moved to Phoenix, where I hope they have a nice kitchen.

In Atlanta, a meal – I want to say it was barbecue because it was in the back yard, but I can’t be sure – with Enrique and my cousin Kirsten. Kirsten’s parents, my aunt Betsey, my father’s half-sister, and uncle Ray, lived next door, having followed Kirsten, Enrique and their kids when they migrated to Atlanta from the Midwest. Aunt Minnie, the other half sister, with whom I share a birthday but even had that not been the case she would have remembered because she’s that way, and who lives near the others but alone, followed next. I don’t want to complain about the food but it has been a frustration, any time I have had occasion to visit that set of households, that by far the best cook in the group is Enrique, who was at that point still running his café in some office park, serving breakfast and lunch every workday, a simple menu but always with a lunch special, so he said I never ate there; he was done for the day with cooking by the time he got home so there it fell to a bunch of Minnesota Norwegians and it was… ok. But I’m not here as a food critic, the meal is more the people than the food, and the gathering was warm.

That’s not quite true, though. I am trying to be gracious saying it’s not the food, it’s the people, etc., but caring about food does bring the people together, and good food is easier to care about. A couple of times I’ve had occasion to work for a few weeks in Chengdu, capital of the Chinese province of Sichuan. Before going the first time I read Fuschia Dunlop’s memoir, Shark’s Fin & Sichuan Pepper, about going to that city to study anthropology at the university, and enrolling in the culinary academy instead: it was a good briefing for my trip, though I did not cook there, I just ate, and watched people eat. They do eat, and talk. They take their time eating, and if conversation flags I think they talk about the food. This the Sichuanese share with the Italians and I’m sure others, people who know their food and take time to appreciate it together. It helps, if you want to do this, to have something in the way the food is served or eaten that slows the pace and encourages the examination of each item. Italians achieve this with a rigid adherence to courses, one dish at a time. Leonardo and I served an American Thanksgiving dinner in Sardinia last year, and had fun instructing our Italian guests to put everything on their plate at once: shocking, but they cooperated in the spirit of furthering international understanding. Chinese, like Americans, are wont to serve many things at once, but while in America that is usually – Thanksgiving, perhaps, excepted - followed by everything being eaten in a hurry, a Chinese meal in company seems to be paced through the judicious handling of chopsticks: watch somebody with chopsticks raised, looking at a dish for the right next morsel, a conscious choice, this small piece of mushroom or that of meat: not that chopsticks cannot be used to shovel something quickly down, but they do facilitate this considered one-piece-at-a-time process, and the attention given to each bite slowing things down and at the same time aiding the collective appreciation of the meal being shared. It reaches its highest form in hot pot, common in Sichuan, two pots actually, one of hot water and one of hot oil, each bite of every vegetable or mushroom or meat chosen by you and then cooked separately while you hold it with your own chopsticks, perhaps then dipping it in a sauce before eating, then on to the next, one bite at a time. What did you do on the weekend?, you might ask someone. Saturday, they’ll say, I had friends over, we made hot pot. Restaurants, big round tables with the pots in the middle, people gathered, taking their time, eating and talking.

But I was in Atlanta, and we were taking our time over some food, I can’t remember what, in Kirsten and Enrique’s back yard. My aunt Betsey was getting quite vague with age, sad to see; uncle Ray keeping track of things, as always. Minnie was there, as I said, and also Erika, Kirsten and Enrique’s daughter. Cousins from my mother’s side, children of my late cousin Pete, dropped in, meeting this lot from my father’s for the first time. Enrique recalled their visit to London, the best thing about it for him, he said, being the summer evening they spent with us and our friends David and Vanessa, David cooking, Nick and Judit also there, sitting together afterwards in the garden, unfolding bits of our lives to one another. Kirsten and Enrique were staying with us in London then. We also had dinner with them at the London restaurant of Enrique’s old and dear friend and co-worker from Mexico, their own connection of dots to which they graciously invited us. One great visit, two meals, there was much more to the visit I’m sure but that’s all I remember.

In Atlanta, we did also make an effort to see the sites, if you must know. Went to the Coca Cola Museum, whoop-di-do.

Dale and Trish, in Nashville, took us out for southern, one might say soul, food, and southern hospitality, another cultural experience for my Europeans. Jeremy had told us, since we’d be stopping in Nashville, where to hear some good bluegrass, and it would have been better to stay another night for that and another meal, but we hadn’t allowed time for that, the journey beckoned. The next three days we drove across the western half of Tennessee, then Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas and the beginnings of New Mexico, in which we saw no friends or family and very little decent food, providing no real dots to connect though just the fact of motel pancake breakfasts served on disposable plastic plates tells me too much about my native land, while the Mexican food we found in Clovis, NM, wasn’t awful but was nothing to write home about. I did get to hear at least a little of the music my son listens to – not much, since on that trip I also introduced him to Tom Lehrer, who entertained us for hours, but at least I heard some of his, which in this day of earbuds we parents don’t hear. I can’t remember what the sounds were, but I’m glad I heard them, another connection made; it happened to be in the car, but as with a meal I’ll claim it as a destination.

Leaving Clovis, we headed west along two-lane US 60 towards Socorro. Somewhere in the sagebrush desert we stopped in a picnic area with two tables and no trees, to have lunch. After a while another car stopped there, travelling the other way. It was a small car, pulling a tidy trailer just large enough to sleep in. The driver was an old man, travelling alone. Not a large man, trim, erect, economical movements. He lived in Iowa now, but for several years had lived in the next town – next for him, it was the one we had just passed through. There was a campsite waiting for him there. He was making a big arc, would be a loop I suppose by the time he got home, from Iowa to various stops in New Mexico and then on to Oklahoma where his daughter lived. He was visiting old friends along the way, he said; or, correcting himself, mostly the children of old friends, since the friends themselves were no longer alive. He warned us about rattlesnakes in the picnic area – the food scraps attracted rodents, which in turn attracted snakes. We were heading, ultimately, for San Francisco, and he recalled his days in the Navy at the Treasure Island base in the middle of that Bay, where he had trained as an electrical technician, work he had carried with him to years of repairing home appliances in the little town he was about to visit, back in the day when a town like that would have an appliance store that employed a technician to repair the goods it sold, a lost world. The sky was darkening, and he was gone, off to his destinations, connecting the dots his life had left scattered. Our highway was following a railroad track and an impossibly long freight train. Lightning started, the heavens opened, we drove on through the downpour toward Socorro.

Socorro as a town is not inspiring. It’s got a small university, so you can get nice coffee, but otherwise it’s within that rural American ambit in which anybody with ambition has moved away. It’s on a corridor of the drug trade, running up and down the Interstate from the Mexican border at El Paso – a stop on the way to Breaking Bad in Albuquerque just a bit to the north. Peter and Jan raised two sons there, and in retrospect I think would have chosen a different town in which to do that: it’s one thing to be in a small town, surrounded by the glories of mountain and desert, when you’re settled in your work, you can have your ties with people elsewhere once you know them and they know what you do. But a place like that is limited, for a teenager.

Peter is Jule’s son, elder of the two and the one still alive. Jule my mother knew from summer camp as a teenager, and as luck would have it her first husband was a physicist who took a job at Stanford and there they were, living two miles from us; Peter is now a professor of geology at New Mexico Tech, the old mining school in Socorro. Jan I didn’t know, though I had read her first book, What Will Fat Cat Sit On?, many times to Leonardo when he was small. House near campus in a comfortable Southwest style, adobe in feeling if not in actual material, like many beautiful things in the west of the US of an aesthetic that marries Spanish colonial – adobe, white plaster, shade from the sun – with Frank Lloyd Wright – horizontal orientation, blonde wood, open spaces, clerestory windows. Outside in a corner formed by two of the faux-adobe walls Peter cooked salmon on a gas barbecue.

The next day he showed us around: a canyon; a mountain with an observatory on top, and a view of a massive array of radio telescopes on the sagebrush plain below; a quaint old mountain town which now has cafes and galleries; a ghost town with iron equipment at the head of an old mine, designed by Gustav Eifel in his pre-tower days, the cemetery in the town filled with Italian names, for many miners came from there. All nice but I need to scour my memory to bring forth those details, while plain as day to me is that that evening we sat with Peter and Jan and their son Willie on folding lawn chairs on a mountainside where they have two small trailers on a little piece of land, eating take-out pizza. The trailers were discussed – Willie’s was very small, like an aluminium exoskeleton into which you could slide a sleeping bag. Peter mused about staking a mining claim on the adjacent public land. Not in any real hope of finding any valuable ore, but because as long as one made a small show of exploring for ore one could keep the land, and thus prevent anybody else from moving in next door on the same pretext. The next day, the three of us, on the road again, had sandwiches on a bench in the square in Santa Fe, I’m not sure what else we saw there before moving on to Taos, where we cooked in our AirBnB. On the way out of Taos, on the north side of town we had breakfast in a restaurant’s courtyard, paying less attention to the food than to the table full of young wildfire fighters, muscular, sooty and alive with exhaustion, for the fire season was underway and we were now on the edge of the forested west. And now, across the Southwest, we saw wonderful canyons but nobody we knew which meant nobody to put their heart into cooking for a meal together and no people, no memorable souls to make the meal itself memorable – that would have to wait another week or two until we got to California, to family and friends, and life could begin again.

I may cause a domestic disturbance, demoting the canyons, as I do, on the grounds they’re not meals, not life. Simona found heaven in the Four Corners and their canyons, she yearns to go back, to see The Arches. I will protest: I did love the canyons, I always love hiking in canyons and mountains and forests. I need forests, in fact, but they don’t need me, I like to think I commune with them but there is no community in it, just me, breathing, and it is a drug, with no lasting benefit, I’ll just need to use it again, walk in another forest, very soon. As for travel to see things – magnificent rocks, places, monuments, forests again, sights: it is an exquisite privilege and I’ll do it again, but it is not connecting any dots, it is not a re-discovery and repair of the web of connections that make my life.

I’ll tell you this story. When I was alone, single, in London, I used to go to a certain Buddhist center to meditate. I met a woman there who seemed nice – regulars at the center were trying to set us up, in fact. I remember neither her name nor what she looked like, but I did go to a party with her, I remember the place, a flat on North Villas in Camden. It was the most boring party I have ever attended, and I say that as one who is often bored by parties. We were a small group of pleasant people, well spoken and probably well educated, living in one of the most exciting cities on the planet. Adults, mostly single, mostly in their thirties, I was in my early forties. My mind’s eye has us seated in a circle. People talked entirely about travel, comparing notes about Places They’d Been. Machu Pichu is the only item from their name-check destination lists that has stuck in my mind. I’ve seen my share of the world but had nothing I wanted to share in that conversation – they had seen things, they were not connecting dots, had no memorable meals or people or conversations to recount; we might as well have been paging through a coffee table book together, admiring the glossy photos. That is all.

I am not, please, looking down on these people, with their tales of Machu Pichu, I am not myself above such travel, travel just to see sights, it may bore me to hear others talk about it but I’ll do it myself. If most of my travel is not that way, but is to connect with people, it is because I have carelessly scattered people, or they have scattered themselves being like me people who move, who migrate just as my parents before me migrated leaving my cousins scattered in their wakes. So I must travel to see the people I want to see. That also makes the trips better than they would be if they were just to see sights, makes for good meals, but that’s an improvement borne of a necessity I have created.

On the next road trip across America, in 2024, the one at the start of which we saw Michael in Washington, Leonardo and I meandered about the Northeast for three weeks, many meals, Leonardo I think gaining some sense of the worlds I had left trailing behind me. Simona caught up with us in Toronto, where we saw a dozen, maybe a score, people, four houses and four dinner tables, old friends of Simona or me or by this point in our lives of both of us. All had relocated to Toronto from someplace else in the world, and those with jobs and children – the exception here being Jane, who is single and retired – having trouble settling into Canadian life. Then we headed west, stopping in Ann Arbor, with my cousin Gaia and his family, and meeting Susan from the old neighborhood in California for lunch. Chicago – no dots to connect there; nice museum, nice river tour - and Des Moines, and then on West. Eileen now lives near Des Moines, not so far, in continental terms, from where the train she and I were riding on derailed half a century ago. She’s a retired doctor, into restoring prairie; their suburban neighborhood has a fair bit of astonishing prairie, tall grasses and all sorts of flowers and insects, flourishing, due to her efforts. On hearing that our next stop would be in the Badlands of South Dakota she assumed we were going there to see more such prairie, that’s what the Badlands are to her, though in fact we had in mind the landforms. The landforms, I can now report, are worth seeing, and the coiled rattlesnake on the trail was another exotic piece of Americana for my two Europeans, but having seen Eileen and her grasses first, the prairie makes the Badlands that much less a stop along the road, and bit more a destination.